Judge Dumitru Rebegea, 35, president of the penal section at Prahova County Court (Tribunalul Prahova), was arrested in November 2009 by prosecutors from the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA–Direcţia Naţională Anticorupţie) for allegedly taking a bribe of €28.000 (US$41,500) to release Zamfir Sandu.

Judge Dumitru Rebegea, 35, president of the penal section at Prahova County Court (Tribunalul Prahova), was arrested in November 2009 by prosecutors from the National Anti-Corruption Directorate (DNA–Direcţia Naţională Anticorupţie) for allegedly taking a bribe of €28.000 (US$41,500) to release Zamfir Sandu.Sandu (aka "Austrianu"), 42, is a well-known member of an organized crime gang who had been imprisoned since July 2009 for blackmail and fraud. According to a press release by the general police inspectorate (IGPR--Inspectoratul General al Poliţiei Române), Austrianu’s family was involved in 22 investigations for fraud, threatening, robbery and grand theft.

At the time of his arrest, Austrianu also illegally possessed firearms. In order to free him, his wife contacted a lawyer (different than the one officially representing him in court), who had worked for several years as a clerk for judge Rebegea before becoming a lawyer. According to the allegations, the former clerk then contacted Rebegea and offered the bribe.

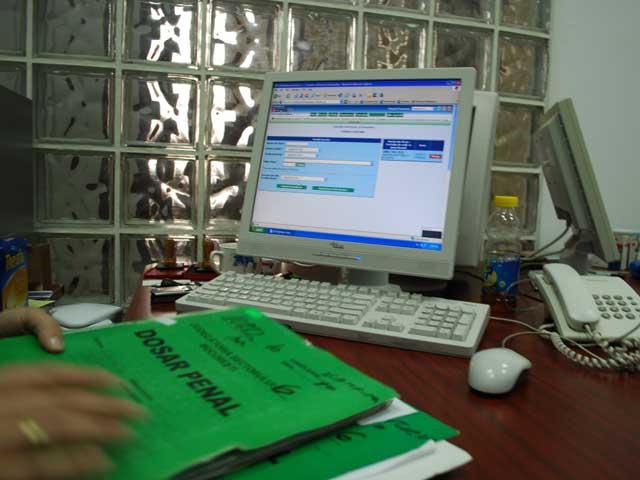

At the end of September 2009, Austrianu was released after Rebegea instructed a lawyer on how to manipulate the software used by the court to distribute cases to judges. The lawyer filed a motion of release on a certain day at a certain hour, making sure the case ended up on Rebegea’s desk.

Soon after Austrianu’s release, Rebegea provided a similar "favor” for Florin Pîrjol (aka Ghenosu), who at the time had been arrested for setting up a blackmailing and scheming organized crime group. The alleged bribe in that case was €20,000 (US$29,600), according to DNA prosecutors.

Helping or Thwarting the Judicial System?

Ironically, just a week prior to Rebegea’s arrest, the Superior Council of Magistracy (CSM--Consiliul Superior al Magistraturii) had made public the results of a nationwide investigation into the manipulation of the case distribution software, called Ecris 3, according to which the system was free from manipulation.

Ecris 3, used to distribute criminal, civil and commercial cases to judges, allows lawyers to file motions of release to multiple judges. The motions land on the desks of several judges at once. When it’s confirmed that a targeted judge got the case, the other motions are withdrawn. Rebegea, familiar with the system, followed the same scenario from prison. He filed several releasing motions, hoping to get a favorable judge to order his release.

Usually, the parties and their lawyers have the option to withdraw the motion before the matter of the file is debated. There are plenty of proceedings to be completed before a case is decided and, depending on the complexity of the case, it can take weeks or even months. This gives the lawyers plenty of time to withdraw the case.

Even when there aren’t bribes involved, an experienced lawyer knows that certain judges will more likely rule in certain ways.

The position of CSM is that magistrates can’t refuse to judge a case on the grounds of repeated filings, as it’s considered limited access to justice.

However, CSM spokesperson, Judge Carmen Georgică, admits the situation is far from ideal: "This gives a bad name to the justice system. It creates tensions and raises suspicions, and a judge can be therefore recused,” she said. Judges can be recused by parties who suspect that something is wrong during the trial.

In 2008, the judges from the First Penal Section of the Bucharest Appellate Court (CAB–Secţia 1 Penală,Curtea de Apel Bucureşti) strongly demanded the standardization of the case distribution procedures.

"Who likes to work in a system permanently accused of corruption, or going to a job where people constantly leer and ask what bribe is involved today? I don’t. There is a limit of supportability,” said Lavinia Lefterache, judge at CAB and deputy director of the National Institute of Magistrates. It was only after the judges’ protests that CAB’s leadership agreed to the standardization.

The software’s failure to detect or alert when a case is filed repeatedly is just one of several problems, along with its inability to recognize new laws or new terms within existing laws. As a consequence, cases involving key regulations -- such as new crimes or the new penal and civil codes -- couldn’t be distributed through Ecris and have to go through traditional distribution mechanisms vulnerable to manipulation.

A Decade of Little Improvement

The implementation of the software in Romania has followed a bumpy road from the start. Its introduction more than 10 years ago in the Timişoara Appellate Court (Curtea de Apel Timişoara) in Western Romania was followed by a decade of reluctance and blockages.

In Romania, the distribution of cases had traditionally been based on no other criteria but the mercy of the president of the court, or the president of a court section. Many perceived this as unfair and uncontrollable, but that has proved a difficult practice to change.

The Timişoara experiment was initially rejected by the judiciary and it was only a few years later that refreshed political will managed to implement it nationwide.

According the Ministry of Justice (MJ–Ministerul Justiţiei), Ecris implementation was compulsory in order to improve the courts’ and prosecutor offices’ activity. The first version of Ecris cost €3 million (US$4 million) and Ecris 3 is now available in all Romanian courts. However, due to various problems, including those described here, it was decided in 2006 that a new version, Ecris 4, was to be implemented.

For €1,65 million (US$2.2 million) more, all the software vulnerabilities should have been eliminated, but four years later the problems continue.

The public tender organized by the MJ for Ecris 4 was adjudicated by a consortium integrated by European Dynamics S.A., a Greek company, and Total Soft S.A., a Romania-registered company owned by a Cyprus off-shore company. The new platform was to be functional in January 2009, but by early 2011 it was still immersed in administrative and technical difficulties.

According to an official MJ document: "The delays were caused by the supplier, European Dynamics, which disrespected the terms of the contract.” MJ and European Dynamics were sued and are presently on trial, but that trial has been temporarily suspended.

Not all the software deficiencies were corrected, and there was a risk the court and prosecutor offices would be blocked from the system and the distribution of cases would collapse. The Supreme Court (ÎCCJ–Înalta Curte de Casaţie şi Justiţie), the General Prosecutor’s Office (Parchetul de pe lângă Înalta Curte de Casaţie şi Justiţie) and MJ negotiated as a group for a special Ecris maintenance agreement with Total Soft, according to the same document.

On Nov. 5, 2010, the Ministry of Justice announced that Ecris 4 was substantially improved, and added that the platform was already functional in one court and would be implemented in all Romanian courts that same month.

Yet, in early 2011, courts were still using the old version of Ecris software and Laura Andrei, judge and vice-president of the Bucharest County Court (TMB–Tribunalul Municipiului Bucureşti), said the court suspended its use until newer problems were fixed. Some of the new bugs include the assignment of extraordinarily long terms for trial (sometimes almost a year), terminology in English, and judges being labeled as clerks.

More importantly, "there were also huge problems regarding the distribution of the cases or when a case was transferred from one court to another,” she added.

Technology or Good Will?

On Nov. 23, 2010, the Ministry of Justice issued another press release saying Ecris 4 has several problems and attributed them mainly to the misuse of the software. No new date for the relaunch of Ecris 4 was set, but the ministry restated that the new software is an essential anti-corruption instrument.

"In other countries, the case distribution is not a subject of such frequent inspection. To dismiss the corruption allegations the judicial system must respond. We impatiently wait for Ecris 4,” said Judge Lefterache.

Virgil Andreieş, president of the Superior Council of Magistracy (CSM–Consiliul Superior al Magistraturii), an institution that guarantees the independence of justice, said Ecris must completely eliminate the issue of repeated motions.

Judge Andrei from TMB agrees, but says this is not a software issue but a matter of good or bad will. "At TMB we have introduced another software program in addition to Ecris that can alert of these practices, which are very common when we talk about motions filed by inmates to be released from prisons,” she says.

While judge Rebegea’s collection of releasing motions have so far failed to get him out of jail on the bribery charges, cases like his and the repeated failures to implement a credible case distribution system only feed Romanian citizens’ and lawyers’ distrust of judges. Common questions like "Why is that judge friendlier to my opponent?” or "Why and how is this perpetrator being released?” don’t seem to be getting any answers anytime soon.